July 4th, 1943

With Flotilla Five On That Unforgettable Day at Rendova Harbor, New Georgia

By Zach S Morris

My grandfather, Stephen Ganzberger, was part of Task Unit 31.9.1—LCI (L) Group Fourteen; Flotilla Five—the Allied landings on Rendova Island, New Georgia on July 4th, 1943 in the South Pacific during World War II. On May 18th 2011, almost 68 years later, he shared with me his recollection of the battle while aboard the LCI (L) 329 that afternoon. I also had the pleasure of interviewing retired Signalman Louis Plant on December 20th, 2013, who was part of the same Task Unit and served aboard the LCI (L) 24. The following piece is written from Stephen’s recollection of his experience and information from Lou Plant’s intricately written “Memoirs of World War II,” that he provided me. Various official documents from various LCIs and LSTs present that afternoon were also used. Information from Eric Hammel’s book, “Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign,” was also referenced. In what turned out to be a desperate effort by the Japanese to halt the advance of the American New Georgia Operation, sixteen enemy bombers attempted to repel the landings of the 169th Infantry with a bombing attack. Three LCI sailors perished, and seven others were wounded that day. Eleven Army Infantrymen were also killed in the attack.

Something awfully peculiar was happening in the harbor of Rendova Island, New Georgia that July afternoon in 1943. The sun was actually shining. D+4 had turned out to be a beautiful day. In the days leading up to July 4, unrelenting rain had punished Rendova Island without mercy from the moment the 43rd Infantry Division arrived on June 30. The rain was cruel and unforgiving. But July 4th was different. The men of Flotilla Five would undergo their baptism of fire on a sunny afternoon—with clear skies above.

As the South Pacific sun set on the evening of July 4th, it cast a shadow over three palm fronds sitting atop three newly dug graves on Rendova Island. The palm fronds had been placed earlier that afternoon by Signalman Lou Plant, and several men from the LCI 24 and LCI 65. They mourned the loss of their comrades who were killed by Japanese bombs just hours before. The names of the men buried in those graves were:

Ernest A. Wilson, BM2c. (Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class)

Mahlon F. Paulson, RM2c. (Radioman 2nd Class)

Hurley E. Christian, F1c. (Fireman, 1st Class)

These are the names of the first LCI sailors killed in action in the Pacific war.

PART I – STEPHEN GANZBERGER ABOARD THE USS LCI (L) 329: OPERATION TOENAILS

Stephen Ganzberger was born on August 25th 1924 in Wyandotte, Michigan. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he waited patiently until the day after his eighteenth birthday—August 26th, 1942—the day in which he enlisted in the US Navy. As fate would have it, he would be assigned to duty in the newly created Amphibious Forces, aboard the USS LCI (L) 329. She was commissioned from Brown Shipbuilding Company in Houston, TX on November 8th 1942. Only a fraction of the size of a traditional Navy warship, she was a flat-bottomed hunk of steel at about one hundred fifty-nine feet long and twenty-three feet wide. The 329’s size and flat bottom ensured the men aboard felt every wave on their vast journey across the South Pacific in spring of 1943. The ride on those particular “small boys” was choppy and rough, as LCIs were not originally designed to cross oceans, but did so out of war’s necessity. It made for a cramped, hot, and muggy lifestyle the entire way. Stephen and his buddies would do their best to relax and enjoy the trip—between bouts of chronic seasickness for the unluckier, less sea-worthy ones. However, one of the better memories that stood out in Stephen’s mind was the sight of Pago Pago, Somoa. He remembered it as the “most beautiful island” he’d ever seen.

Seaman 2nd Class Stephen Ganzberger and the crew of the LCI 329 arrived at Lunga Point, Guadalcanal on the morning of June 27, 1943. At that time, the Allies were just beginning the seizure of their next major target in the South Pacific—New Georgia Island. The crew of the LCI 329 had arrived in the Solomon Islands just in time for the opening days of the New Georgia Campaign—dubbed “Operation Toenails.”

The New Georgia Campaign just happened to be an extraordinarily special landmark for the Amphibious Forces as well. It was the first campaign in the Pacific in which the Americans utilized LCIs to land troops on enemy beaches. Any engagements with the Japanese would be among the first combat seen by LCIs in the Pacific Theater.1

Just to the south of the main island of New Georgia, lies a tiny island called Rendova. Despite its rather meager size it was crucial that the Allies capture it. Rendova’s location made it one of the critical islands needed for artillery support as the Americans drove towards their objective—Munda Airfield—located several miles across the channel on the southernmost tip of nearby New Georgia Island. Munda’s seizure would not be possible unless Americans controlled Rendova. On June 30, 1943 the first landings on Rendova began. The first few days that followed did not go as planned for the 43rd Infantry Division and Admiral Turner’s Western Landing Force, as torrential rain bogged down the infantry as they landed and attempted to unload equipment and supplies on Rendova’s northern beaches. It had been a messy disaster.

But Stephen and the crew of the USS LCI (L) 329 would make their first landing of the war on a sunshiny day—July 4, 1943.

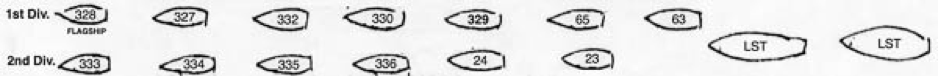

LCI (L) Flotilla Five’s Group 14—led by Lieutenant Commander A. Vernon Jannotta on the flagship LCI (L) 328—sailed in two columns to the northernmost tip of Rendova Island, through the Blanche Channel, in the early morning of July 4 under the cover of darkness. Thirteen LCIs then squeezed southward, through the narrow Renard Entrance, entering Rendova Harbor at around 8:00 AM. Stephen’s LCI beached with the first group of LCIs at around 10:00 AM on Rendova’s East Beach. The ramps on each side of the LCI 329 lowered, and began to discharge the troops and equipment of the 169th Field Artillery Battalion.

However, the Japanese had other plans for the landings of Flotilla Five.

* * *

Meanwhile, about four hundred miles to the northwest of Rendova Harbor, the enemy fortress of Rabaul was scrambling in preparation for battle. Rabaul, the mighty Japanese air base—located on New Britain Island, just off the coast of Eastern New Guinea—was the epicenter of Japan’s naval and air power in the South Pacific at that time. Pilots rushed to their planes. Japanese Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, commander of the 11th Air Fleet was determined and desperate to halt the American advance in the New Georgia Island Group. In a last-ditch effort, Kusaka ordered an aerial assault in hopes of disrupting American shipping and supply locations. About one hundred Japanese planes, including sixteen dual-engine Mitsubishi Sally and Betty bombers, took off en route to the southeastern Solomon Islands.2

Their target—the Allied landing force beached at Rendova Harbor. An epic encounter was about to ensue.

PART II – THE BOMBING RAID: LOUIS PLANT ABOARD THE USS LCI (L) 24

By 12:30 PM the first group of LCIs (329, 334, 330, 335, 328, 327, 333, and 336) had completed unloading the men of the 169th Infantry and had made their way off the beach. Some moved to the northern end of Rendova Harbor. The remaining five LCIs—consisting of the second group—replaced the first group of LCIs on the beach. The second group consisted of the LCIs 23, 24, 65, 63, and 332 (the 336 part of the first group, remained stranded on the beach). As the second group unloaded their troops, they noticed a battle had begun in the air above Munda Airfield on southern New Georgia Island, to their north. American fighter planes were engaging incoming Japanese planes in dogfights at around 1:50 PM. The fighting intensified with each passing minute.

* * *

Over on Baraulu Island, a tiny island located across the Blanche Channel about six miles to the north of where Stephen’s LCI 329 was currently anchored, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Shafer was in the process of setting up 155 MM howitzers with the rest of the 136th Field Artillery Battalion that he commanded. He looked up into the western sky and noticed about a hundred enemy planes were approaching the massive umbrella of American fighter planes that had gathered over Munda Airfield.

Like the hunter that waits for his prey to enter a trap, the Americans were waiting in the skies above Munda. Waiting to ensnare Vice Admiral Kusaka’s air force.

Shafer witnessed the run of the sixteen surviving bombers flying in a stepped-up vee-of-vees formation. They were the only ones that managed to make it through the onslaught of dog fighting American fighters waiting for them. The sixteen bombers flew right over Shafer’s head, but he could not see the insignias on the bombers. They curved slightly towards the southeast, then all the way around to the right until they were flying due west towards Rendova Island. Suddenly, Shafer realized the bombers were enemy Japanese. Although not aware at the time, Shafer had a ringside seat to what was about to be an incredible spectacle.3

* * *

As Shafer watched the enemy bombers from Baraulu Island, Stephen was loading rounds into a 20MM gun for the gunner and his good buddy—Ship’s Cook 3d Class Elmo Pucci. They both looked up from the LCI 329 not expecting to see the sixteen low-flying Japanese bombers that suddenly appeared over the eastern horizon. The Japanese bombers were heading straight for them.

At 2:05 PM, every single American artillery gun on Rendova Island opened up with their very own fireworks show at the exact same time. Every LCI and LST in the harbor and on the beach also commenced firing soon thereafter. Stephen described the eruption of anti-aircraft fire from below that blossomed blackly within the bomber V-formation.

We took the troops in. And the moment we dumped them off, we backed out and turned the ship around. And when I looked up in the air, here comes sixteen bombers at three thousand feet. And man that’s all I kept doing was pouring bullets up there. I must have gotten one or two of them.”

The sight of thousands of flashing tracers that upwardly pierced the sky was quite a sensational sight. There was no escape from the curtain of Allied fire that met the Japanese bombers from all directions below. Stephen soundly recalled:

[The bombers] was right on top of us. You couldn’t miss em’ if you tried. I just kept going and pulling sixty rounds. I told [the gunner] Pucci, ‘Keep pumpin until that barrel gets hot!’”

Bomber after bomber fell away in flames. But tragically, due to their low-altitude flying, they had managed to release their bombs just before the anti-aircraft fire reached them. The enemy had passed directly overhead the LCIs and LSTs anchored and beached in Rendova Harbor. The harbor was engulfed in fire and shrapnel was flying everywhere. But it was shrapnel from a bomb that exploded between the LCI 24 and LCI 65, which would cause the first combat casualties of LCI sailors of the war in the Pacific. Three LCI sailors lost their lives, and seven were injured from that bomb, which ripped holes in their hulls and badly damaged both ships.

Louis V. Plant, one of the two Signalmen aboard the LCI 24, witnessed a scene he’d never forget. Shrapnel from Japanese bombs took the lives of two of his shipmates that day. The first shipmate taken was a quiet, older Boatswain’s Mate—Ernest Wilson. Lou described it years later in his memoirs in vivid detail:

I look forward and I see Wilson lying on his back screaming because the hot deck is burning his flesh. His eyes roll back in his head and he dies from shrapnel wounds. The Quartermaster climbs up on the bridge and says, “Paulson (our radioman) is dead, sir.” 4

The Quartermaster was referring to Lou’s friend, the second man killed—Radioman Mahlon Paulson—who was curious as to what the deafening commotion from all the anti-aircraft gunfire was about. Paulson had left his radio to find out, instead of hitting the deck or taking cover. In Lou Plant’s memoirs he wrote:

I climb down from the bridge and head for the ‘Radio Shack.’ Paulson is lying there. He had left his radio to see what the firing was all about instead of hitting the deck and trying to find some kind of cover. A chunk of shrapnel had hit him square in the face and tore most of his head off. The force of the bomb blast had knocked him backward into the ‘Radio Shack.’ Had he stayed at his radio he might have escaped with just being wounded […] I look down on the Port side and see a soldier who has been cut in half above the knees by shrapnel. He says, ‘Guess I’ll get the Purple Heart for this’…and he dies.” 5

Four other sailors aboard the LCI 24 were wounded and two Army soldiers were killed below deck. Another Army soldier was killed while standing on the beach amid the port side of the LCI 24—right next to another wounded soldier who, somehow, survived the shrapnel. The LCI 23, which was beached next to the LCI 24 (starboard side), also suffered three casualties from fragments of a 100-lb. anti-personnel bomb.

The LCI 65, located on the other side of the LCI 24 (port side), would see one of her sailors killed that afternoon while he was manning the No. 4 gun. Fireman Hurley Christian was struck in the forehead and killed by a flying bomb particle.

Despite the destruction from the Japanese bombing run, the Allied forces inflicted severe damage on the enemy bombers. Out of sixteen, twelve were eventually confirmed shot down—five enemy bombers on the first pass, three on the second pass, and four on a third pass attempt. Other reports claim American fighter planes finished off the four remaining bombers as they looped around over Munda Airfield.

Later on in the afternoon of July 4th, Signalman Lou Plant was ordered to take his buddy Mahlon Paulon’s body ashore and bury him. As Lou recalled in his memoirs:

This was one of the toughest things I have ever had to do, digging a grave for a shipmate with whom you made liberties back in the States. By this time, people are bringing bodies ashore from several ships.” 6

The three sailors were buried together on Rendova Island about a quarter mile east of the landing beaches. Lou spoke of the unnerving stench of death that accompanied them as they buried their fallen crewmen. He and his buddies gently placed Paulson’s body into a shallow grave and covered it with dirt. They placed palm fronds on top of the dirt before returning to the LCI 24. Lou somberly remembered that after that day, the men who had been so eager to see combat, never again asked when they were going to see some action.

Despite what would prove to be a deadly and grueling struggle, the Americans would hold Rendova, capture Munda Airfield across the channel, and secure the rest of the New Georgia Islands.

After the Solomon Islands Campaign, Lou Plant returned home and was assigned as Staff Signalman aboard the LCI 484—part of LCS(L) Group Seven under the command of Commander F.P. Stone. He would later participate in the Iwo Jima and Okinawa Campaigns. Stephen Ganzberger was transferred for duty aboard the LCI 65 as a Quartermaster in January 1944. He would later participate in the Dutch New Guinea and Philippine Islands Campaigns. He was honorably discharged on August 15, 1945, the day Japan surrendered to the Allies.

LCI Flotilla Five’s first encounter with the enemy had come at last—and on July 4th of all days. There was no shortage of examples of the men’s bravery and fighting spirit in the official reports detailing the events of that afternoon. Lieutenant James McCarthy of the LCI (L) 63 wrote of his men’s determination in keeping up their fire even when enemy bombs were hitting close by. B.A. Thirkield of the LCI (L) 23 wrote that his crew, most of whom were under enemy fire for the first time, performed excellently. But perhaps the most stirring account of the men’s resolve are the words written by Lou Plant’s skipper, R.E. Ward—the commanding officer of the LCI (L) 24 who lost two of his own men that Independence Day. In his official action report detailing the events of 4 July 1943, Ward concluded by saying:

The officers and enlisted personnel fought the ships guns and fires without regard to their personal safety. For a new crew in their first action, they worked quietly, efficiently, and with valor. Individual initiative, courage, and cooperation represented that of the highest traditions of the Navy.” 7

Author’s Note:

– Retired Signalman Lou Plant currently lives in Livonia, MI.

– Stephen Ganzberger passed away on May 20, 2011, two days after he shared his story with me. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He will always be my hero.

SOURCES:

1 Landing Craft, Infantry and Fire Support (Rottman, p. 43)

2 Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign (Hammel, p. 77; Crown Publishers, NY)

3 Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign (Hammel, p. 77; Crown Publishers, NY)

Lou Plant and Lieut. Col. Henry Shafer identified the 16 Japanese bombers as Bettys (Mitsubishi land-based G4M Bombers). However, the official Action Reports I obtained from 4 July 1943 from the LCI’s, and several LST’s, state that the 16 bombers were identified as Sallys (Mitsubishi Ki-21 Type 97 Heavy Bombers). It is entirely possible that both types of bombers were present. Lou Plant remembers only one of the sixteen Japanese bombers being destroyed.

4 Memories of World War II by Louis V. Plant (p. 17)

5 Memories of World War II by Louis V. Plant (p. 17)

6 Memories of World War II by Louis V. Plant (p. 18)

Records of the Chief of Naval Operations: National Archives, College Park, Maryland:

7 Official Action Report: U.S.S. LCI (L) 24; July 4 1943 (File 101439; pages 9-10)

*Others relevant documents referenced:

— Action Reports: Commander, S. Pacific Serial 2190 dated Oct 17, 1943: Anti-Aircraft Action During Landings at Rendova and Vella Lavella (25 pages); 370/44/20/04: Box 73

— USN Deck Log, U.S.S. LCI (L) 329 – June-August 1943 – 470/37/08/01: Box 946

— War Diaries, U.S.S. LCI (L) 329 – June-August 1943; 370/46/05/07: Box 1040

— Combined War Diary and Log, U.S.S. LCI (L) 65 – July to September 1943; Reg. No. 2190-N (Pages 3-6)

— Official Action Report: U.S.S. LCI (L) 332; July 4 1943 (File No.56278; pages 1-2)

— Official Action Report: U.S.S. LCI (L) 328; July 4 1943 (File No 55695; pages 25-36)

Mark

Wow, My wife’s grandfather was serving on LCI-334 mentioned in this article. I wish he had told us more while he was alive. He passed away 25 Jan 2019.

Stan Galik

Mark: Thanks for identifying your wife’s grandfather as Cleland W. Popke, SM 3c who served on the LCI-334 and passed away on Thursday, January 24, 2019.

Dave

I believe that my uncle, George Washington Chandler, was killed on this day during this bombing.

CHANDLER, George W, F3, 6025414, Amphibious Boat Pool 8, New Georgia, Rendova, Vangunu occupation, July 4, 1943, (CasCode121) killed in combat, dd July 4, 1943

Robert L Koentz

My uncle John Elmer Cicotte F1c, LCI (L) #24, related this same story to his son Rodger Cicotte prior to his passing on April 6, 1978, his memory of this event had stayed vivid in his mind for all the ensuing years. May God bless all those great men and women who fought to give us the freedom we have enjoyed all these years!

Zach Morris

Robert,

I just published a WWII book on LCIs which elaborates on this article. The book also features interviews from veterans who served aboard the LCI 24, and features stories about the LCI 24. Check it out: https://amzn.to/3INdNDM