By John France, Historian, USS Landing Craft Infantry National Association

On June 6, 1944, U.S.S. LCI(L) 85 sailed through rough waters towards the Normandy Coast of France. LCI 85 was part of a vast armada of more than 5,000 ships and landing craft underway to deliver an army to liberate France from Adolph Hitler’s occupation forces. From France, the allies would push into the heart of Germany and end the most devastating war in human history. The seasoned officers and crew of LCI 85 were combat veterans of the invasions of North Africa, Sicily and Salerno, Italy. They were part of the fabled LCI Flotilla 4, consisting of 24 LCIs manned entirely by U.S. Coast Guard crews. Upon their transfer to England, the “Coasties” of Flotilla 4 joined twelve U.S. Navy LCIs to form Flotilla 10 for the Normandy invasion. On board LCI 85, was a crew of four officers and 30 enlisted men, including two additional Pharmacist Mates (medics) who were temporarily assigned to LCI 85. Allied planners of “Operation Neptune,” the code name for the seaborne invasion of Normandy expected high casualties.

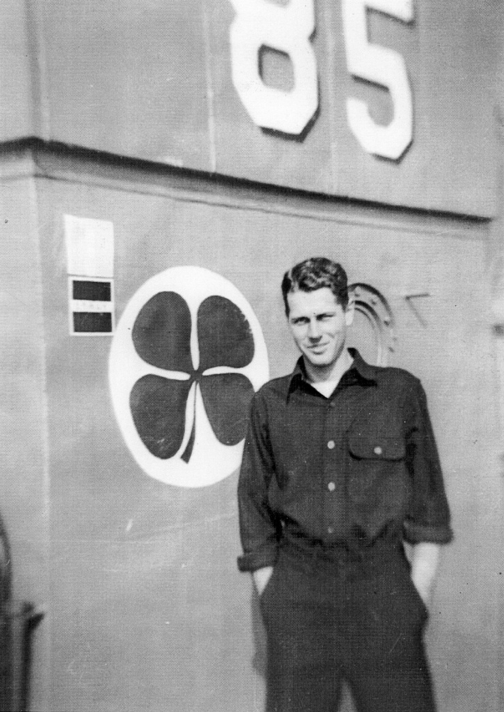

On the conning tower of LCI 85 was painted the crew’s good luck charm, a Four- Leaf Clover. It had served them well, keeping them safe through previous invasions. One particular incident of LCI 85 luck occurred during the night of September 7, 1943 in the bay of Palermo, Sicily. There, a German aircraft dropped a torpedo which passed amid-ship directly underneath LCI 85, narrowly missing her due to her shallow draft. The torpedo continued on and struck a Landing Ship Tank (LST), which exploded and burned.

On D-Day, the 189 soldiers onboard LCI 85 were seasick and miserable. They had been in cramped quarters for several days because the invasion, originally scheduled for June 5, had been postponed due to stormy weather. The soldiers on board consisted of troops from the following units: Company C, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, 5th Engineer Special Brigade – 26 personnel; Company C, 6th Naval Beach Battalion – 40 personnel; 210th Military Police Company – 13 personnel; 294th Signal Company – 10 personnel; Headquarters and Service Company, 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, 5th Engineer Special Brigade – 4 personnel; Company B, 6th Naval Beach Battalion – 7 personnel; and Company A, 1st Medical Battalion – 89 personnel.

The Skipper of LCI 85, Lieutenant (j.g.) Coit Hendley Jr., was familiar with the troops on board. LCI 85 had landed them during practice runs at Slapton Sands, Devon, England. They included Combat Engineers consisting of both Navy and Army personnel, whose job it was to clear beach obstacles, mark beach exits and organize the unloading of men and supplies from landing craft. The Executive Officer of LCI 85, Lieutenant (j.g.) Arthur Farrar noted that two of the doctors on board were veterans of the Tunisian Campaign. One had been awarded the Silver Star Medal and the other had been awarded the Purple Heart Medal. Their job on D Day was to set up a first aid station one mile inland from the beach.

The Silver Star Medal recipient was Captain Emerald M. Ralston of Company A, 1st Medical Battalion, 1st Infantry Division. He was born in Oberlin, Kansas on April 25, 1906. He graduated from John’s Hopkins School of Medicine. Before the war, he lived and worked in Warren, Pennsylvania. He was 38 years old, much older than most of the men assembled to assault the Normandy beaches.

Hendley, 23 years old, was a Southerner with a distinct southern accent. He was born July 17, 1920 in Columbia, South Carolina. His father was a bank president. Hendley began his studies at the University of South Carolina in 1936 at age 17. He graduated in 1939. Hendley moved to Washington, D.C. where he began work as a copy boy in 1940 with the Washington Evening Star newspaper. He joined the U.S. Coast Guard February 18, 1942 in order to make a contribution to the war effort. Hendley, like many others who joined the Coast Guard, expected to spend his time during the war patrolling the U.S. Coastline. He was wrong.

Hendley was assigned to LCI 94 of Flotilla 4 in Galveston, Texas as the Executive Officer. He participated in three invasions with Flotilla 4 and sailed with them to England. There, he was promoted and took command of LCI 85 on January 13, 1944. He replaced Lieutenant Thomas R. Aldrich as skipper. Hendley’s reputation preceded him. During the invasion of Sicily, the troops were hesitant to descend the ramps under enemy fire. Hendley observed this from the bridge. He rushed down, pushed by the soldiers and marched down a ramp as if it was a drill. Either embarrassed or inspired, the soldiers followed him.

Hendley enjoyed life in England while awaiting the invasion of Normandy. Comfort in England included a girlfriend, Wren Sylvia Grashoff. She was a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service.

Farrar was 30 years old. He was born July 12, 1913 in Graham, Texas and was raised in Elgin, Oklahoma. After graduating from college, he was a school teacher and by 1940, he was the Superintendent of Schools in Elgin. Farrar left his job July 1, 1942 and seven days later enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves in Nashville, Tennessee as an Apprentice Seaman. After completing a competitive exam, Farrar was transferred October 10, 1942 to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut for Reserve Officer’s Training. He joined LCI 85 in Galveston, Texas, February 1942 and four months later, he was sailing off to war.

By the time LCI 85 sailed to England, Farrar had two souvenir German machine guns stored in his locker from previous invasions. He frequently practiced marksmanship with his Government issued, Navy 45 caliber, 1911 semi-automatic pistol. He nearly shot smooth the bore, shooting at unsuspecting sharks and seagulls. This combat veteran was ready for Normandy.

The only other “Okie” on board LCI 85 was Coxswain Elmer Carmichael. He was 23 years old, born May 19, 1921 in Tonkawa, Oklahoma. Carmichael moved with his family to Crescent, Oklahoma in 1927, where his father was City Marshall for many years. Carmichael graduated from Crescent High School 1940. He was president of the senior class, president of the student council and graduated as salutatorian. After high school, Carmichael worked at the Crescent Lumber Yard until he joined the U.S. Coast Guard on June 21, 1942. He met Farrar when Farrar joined LCI 85 in Galveston, Texas. They bonded during a long conversation on deck. From then on, they worked the same watch together on board the “85”.

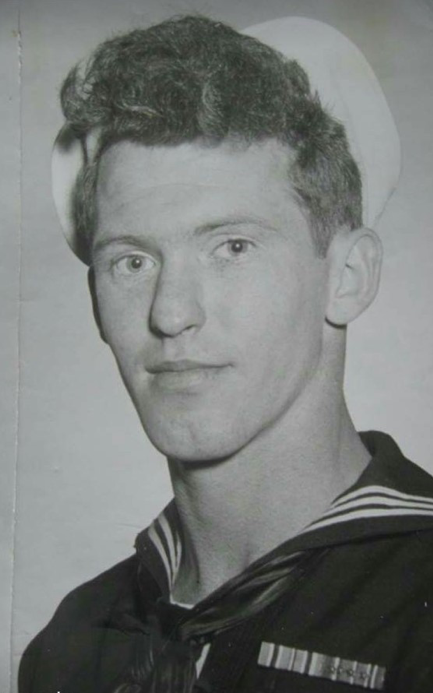

Seaman 1st Class Gene Oxley

Another crewman on LCI 85 was Seaman 1st Class Gene Oxley. With freckles and blue eyes, he stood 5’ 8”and weighed 130 pounds. He was 20 years old, born October 21, 1923 in the small town of Stilesville, Indiana. He was the youngest of six children. When he was four years old, his father committed suicide in front of the entire family. Gene was very close to his mother who was devastated by her husband’s suicide. She was a frequent patient in mental institutions.

Oxley’s older sisters – Mildred, Mabel and Dorothy, all helped raise Oxley until they married and moved out of the house. Oxley persevered. He began swimming shortly after he could walk. He went swimming in all the local swimming holes whether swimming was permitted or not. Later, the family moved to Indianapolis where he joined a Y.M.C.A. He was a life guard at a local park. He was a Boy Scout and earned good grades in school. Oxley’s family moved back to Stilesville where he graduated from high school in April 1942. He joined the U.S. Coast Guard in Indianapolis on July 17, 1942.

In England, at the end of May 1944, Hendley received a fifteen- pound canvas bag that was sealed and marked “TOP SECRET.” With the bag was a dispatch advising him not to open the bag until ordered to do so. He only had to wait a few days to receive the order to break the seal and open it. Inside the bag were orders, the plan of attack, maps, charts, and photographs of their targeted beaches. The troops who boarded LCI 85 in Weymouth on June 2nd were ordered to remain on board along with the crew of the “85” until it was time to sail. Secrecy was strictly enforced. Nobody could leave LCI 85 without having specific business to conduct, and without being escorted by an officer. Hendley had more than a week to study the plans.

All Flotilla 10 LCI Commanders met in the hold of the Flotilla Flagship where a detailed map was painted on the wall and deck. The map depicted their target, the beach sectors and landmarks of Omaha Beach as if viewed from ten miles off shore. With briefing and training complete, all that remained was the tense waiting.

General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces for “Operation Overlord,” the air and sea invasion of Normandy, gave the orders for D Day to commence on June 6th. Thus, began what Eisenhower referred to as the “Great Crusade” to liberate Northern Europe from the Nazis. A special double daylight savings time was established for D Day. Therefore, it did not get dark until 11:30PM. LCI 85 and Flotilla 10 set sail from Weymouth at 3PM on June 5th and sailed the majority of the way across the English Channel in daylight with overcast skies.

From midnight on, Farrar observed air activity over France. Cones of flak of various colors lit up the sky. Many expected to be bombed by German aircraft or attacked by torpedo boats during the voyage, but it did not happen. Flotilla 10 split with half of her LCIs headed for Utah Beach and half headed for Omaha Beach. By 3AM, the transport ships and landing craft had arrived at the assembly area, 20 miles from Omaha Beach. By 4AM, LCI 85 was circling in her assigned position, awaiting orders to head for shore. At 7:30AM, she headed full speed towards the battle.

LCI 85 was scheduled to land troops on Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach, at 8:30AM during half-tide when many of the beach obstacles were exposed. Omaha Beach was two miles long and Easy Red sector was located in the eastern half. There were few signs of trouble ahead. The beach was shrouded in smoke and Hendley observed some black puffs from explosions along the shoreline. On schedule, a control vessel signaled the “85” to proceed to the beach. With Hendley on the Conn and Ensign Harold C. Mersheimer standing next to him, LCI 85 plowed through the waves at twelve knots.

Chief Quartermaster Charles O. McWhirter was at the helm in the wheel-house below Hendley. Ensign Paul M. Petit, the Engineering Officer, stood at the winch on the stern. His job was to let the stern anchor out as they neared the beach so they could winch themselves back off the beach after landing the troops.

Farrar was stationed between the two ramps at the bow. He was in charge of landing the troops. He and Carmichael, who manned one of the ramps, stood a few feet from each other. Carmichael had a lot of confidence in Farrar and was impressed with Farrar’s coolness under fire during previous invasions. As the “85” pushed through the rough seas, Farrar and those manning the ramps were soaked by waves splashing over the bow.

As LCI 85 neared the shoreline, signs of a deadly, chaotic battle came into view. Numerous small landing craft careened about and many had been hit by enemy fire. Hendley directed McWhirter to steer the “85” through a small opening in the beach obstacles. Adorned with her Four- Leaf Clover, LCI 85 made her final push. Hendley could see a line of prone soldiers along the beach firing at German positions. Four American Sherman tanks were directly ahead. Three were ablaze and the fourth fired at the enemy intermittently but appeared to be disabled.

Due to the strong cross current, LCI 85 landed farther east than planned on Easy Red, near Fox Green beach sector. The “85” crushed through obstacles and ground to a halt short of the beach. It was stuck on top of an unknown obstacle. Farrar ordered the ramps lowered. Oxley scurried down the ramp with a light tow line around his waist that was connected to a 30-pound anchor and a heavier rope – the “man rope.” His job was to anchor the man rope on the beach so that the soldiers, laden with heavy equipment in the rough surf, could pull themselves to shore. Oxley volunteered for this dangerous task as he had done so before during the invasion of Salerno, Italy. When Oxley jumped off the ramp, he immediately sank over his head in water. Clearly, troops could not be landed there. The soaking wet Oxley was hauled back aboard and Hendley ordered the “85” to be retracted from the beach so that they could attempt another landing elsewhere.

While retracting, LCI 85 was struck by three artillery rounds from German shore batteries. One round penetrated troop compartment # 3. McWhirter could hear through the voice tube in the wheel house the screams of the soldiers below deck. During retraction, something hit the stern winch and disabled it. Petit would not be able to drop the anchor to assist retraction during the next beaching.

LCI 85 rammed through obstacles a second time and beached approximately 200 yards to the west on Easy Red beach sector. When the “85” grounded about 70 yards from the beach, it struck a teller mine on an obstacle, which exploded under the bow. The explosion fractured the forward compartment and water poured in. When the ramp crew attempted to lower the ramps, only the port ramp hit the water. The starboard ramp became stuck on top of a beach obstacle.

Once again, Oxley dashed down the ramp and into the water with the man rope. This time it was only waist deep at the end of the ramp. He swam with the line through withering machinegun fire. Each time, he attempted to duck under water to avoid the bullets, his life belt popped him back up. The strong cross current pushed Oxley east as he swam. When he reached land, he found that he was far off course from the bow of LCI 85. He ran exposed on the beach back to a point directly inland from the bow. He began pulling out the slack of the man rope only to discover that the anchor had been shot away.

Hendley observed soldiers who had been prone on the beach, stop their firing to assist Oxley pull the rope taut while another soldier fired a bazooka at the Germans. Because there was no 30 – pound anchor attached to the man rope, Oxley turned his 130 – pound body into an anchor. He wrapped the man rope around his waist and dug his heels into the beach. Although, the Germans continued to shoot at him, he stood there alone holding the rope taut and awaited the troops to descend the ramp of LCI 85. He was amazed that the hail of German bullets did not strike him.

Even though Oxley encountered deeper water closer to shore, Hendley decided to disembark the troops. Soldiers began descending from the ramp. Heavy German machinegun fire swept the water and the hull near the ramp filled with troops struggling to get ashore.

After Oxley saw a group of four men descend the ramp, he observed the ramp twist off from what he believed to be a hit from German artillery. Soldiers toppled off the ramp. Farrar who stood mere feet from the ramp, observed the ramp get twisted off by the strong cross current. It dropped five feet, held only by the cables from the forward winch. In total, Oxley observed 36 soldiers disembark from LCI 85 via the ramp or by lowering themselves over the side. They struggled through the surf holding on to the rope. Oxley, steadfastly holding the other end of the rope, watched in horror as German machine gunners raked straight down the line of soldiers. Oxley saw only six soldiers make it to the beach.

During this time, the Germans pummeled LCI 85 with many artillery rounds from various cannons including their dreaded 88 Millimeter. Originally designed as an anti-aircraft flak gun, the Germans used it effectively in a number of roles. It was their best artillery piece, and the “88” overlooking LCI 85 wreaked havoc on her.

The Germans concentrated their artillery fire on the forward section of the “85” where the massed troops awaited to go down the ramps. Oxley, who believed that Hendley was the best skipper afloat, stated that the Germans “shot away everything around him on the exposed bridge but he stayed right up there without even taking cover once.”

Hendley who had just waved at two of his friends standing below him at the base of the conning tower, watched both of the officers killed instantly by one artillery round that also wounded several others on the crowded deck. Killed in that blast were officers of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion, Beachmaster Jack Hagerty and Beachmaster G.E. Wade. Onboard LCI 85, three other members of the 6th Naval Beach Battalion were killed – Assistant Beachmaster, Lieutenant (j.g.) Leonard Lewis, Boatswain’s Mate George Abbott and Pharmacist’s Mate John O’Donnell.

As soon as the artillery rounds began slamming into the “85,” Captain Ralston of the 1st Medical Battalion jumped into action. Two troop holds below deck were set afire. Ralston rushed down into one of them. There, he calmed the men and organized them to fight the fire. Although suffering from a painful burn to his face, and struggling against extreme heat and heavy smoke, he performed life- saving medical treatment on the wounded. He continued his heroics by pulling a critically wounded out of the other burning troop hold. In the meantime, shells burst through the wheel house and blew the clothes off of McWhirter. Miraculously, he only suffered a narrow scratch down his back.

Farrar also had a very close call. While working the ramp, he was grazed in the left thigh, which took off a chunk of his left buttocks, creating a large flesh wound. He looked down and saw a hole the size of his head in the hull of the “85” from the artillery round that nearly killed him. In pain, he removed his gun belt with his trusty .45 caliber semi-automatic pistol and went back to work.

Other than the scratch on McWhirter’s back, there were no small wounds on LCI 85. There were chunks of flesh, heads and limbs covering the deck. Ralston and other medical personnel administered plasma to the wounded and patched them up the best they could.

Of the four wounded crewmen of LCI 85, the most serious was Radioman 3rd Class Gordon R. Arneberg. An artillery round ripped through the radio room and tore off one of his legs. He was dragged out of the room and onto the deck and were he received medical treatment. His severed leg was one of the obstacles for Hendley and others to negotiate around until someone kicked it overboard. Soldiers remaining on board could not move forward through the bodies and the blood- slick deck. With her ramps out of order, landing troops from LCI 85 came to an end.

Hendley gave the order to retract as fast as possible. Oxley saw LCI 85 retracting from the beach and he held on to the man rope as he ran towards her. However, the German steel raining down on him forced him to drop the rope and run back to seek cover. Oxley was left behind on the beach.

As LCI 85 retracted, the wounded Farrar climbed down onto the ramp in an attempt to rescue the wounded soldiers clinging to it. He pulled one man onto the ramp and held on to him. Another soldier clung to the ramp without assistance. Farrar tried to pull a third soldier up but the terrified man had a death grip on a lower stanchion of the ramp. Farrar could not break the soldier’s grip. Farrar realized that he could not save the man and let him go. Farrar and the other men on the ramp had a rough ride during the fast retraction away from the German guns. They got dunked several times into the waves as they clung to the dangling ramp.

When LCI 85 stopped, Farrar crawled back onto the deck and Boatswain’s Mate Rudolf D. Hesselgren helped him drag the two remaining soldiers aboard. They discovered that one of them had succumbed to his wounds. Boats came alongside LCI 85 to rescue wounded and transfer the remaining able-bodied soldiers to shore. Ralston transferred wounded to one boat that came alongside to the rescue. The crew of that boat implored Ralston to come aboard. He refused. Instead, he ordered the remainder of his unscathed team members to board a Landing Craft Medium (LCM). They were transported to shore under heavy fire. Ralston was wounded while underway. He refused medical treatment and tended to the wounded on shore. Several times, under heavy fire, he rushed from the beach into the surf to rescue wounded soldiers and drag them to relative safety.

After navigating LCI 85 away from the German guns, Hendley descended from the conning tower with Pharmacist Mate Simon Mauro to count the casualties and assess the damage. LCI 85 had been hit by 25 German artillery shells. They counted fifteen dead and 30 wounded on deck. Hendley decided to get the wounded to a medical ship.

Three fires burned below in the forward compartments as LCI 85 limped seaward towards help. The crew of the “85” put out the fires and feverishly worked pumps to remove the water from the battered holds below. Pumping out the water was an important delaying action to keep LCI 85 afloat but in the end, it would be a losing battle.

Ten miles off shore, LCI 85 came alongside the USS Samuel Chase, a transport ship, manned by “Coasties.” U.S. Coast Guard combat photographers on board, documented the event with still photos and a movie of the crippled “85.” Hendley transferred the wounded, including Farrar, to the “Samuel Chase.” Carmichael overheard a conversation between Hendley and an officer on the “Samuel Chase.” Hendley demanded that the officer take the dead off LCI 85. The officer refused and told Hendley to take the dead back to shore. Hendley replied that the “85” could not make it back to shore. He argued that if the officer did not remove the dead from LCI 85, nobody would ever know what happened to them. The officer finally gave in and the dead were transferred. Carmichael was very moved by Hendley’s effort to secure and respect the men killed on board his ship.

Some Navy and Army doctors who were transported to the beach by LCI 85, remained onboard to treat the wounded until they could be transferred to the USS Samuel Chase. With that task completed by 1:30PM, they boarded a small boat in silence and were transported back to the hell of Omaha Beach where they knew they were needed.

Meanwhile on shore, Seaman1st Class Oxley dug a shallow foxhole with his bare hands and feet on a very narrow strip of beach clogged with soldiers. They could not advance any farther without being cut down by enemy fire. Oxley was unarmed, barefoot and had lost his helmet. The tide began to come in and Oxley dug several more foxholes as he tried to stay ahead of the surging water. The soldiers around him did the same. Eventually, the water forced them over a three- foot high sandbar where they were completely exposed to German snipers. They dug in the best they could but the Germans found their mark over and over. Oxley conversed with a medic with his head down in a foxhole next to him. At one point, Oxley asked the medic what type of aircraft was flying overhead. When he received no reply, Oxley lifted the medic’s helmet and saw that he was shot dead.

Tanks were unloaded from landing craft. Soldiers hugging their shallow foxholes saw the tanks as better protection from the German gunners. They got up, ran and huddled behind the tanks. Oxley was fortunate he did not join them. One by one the tanks were destroyed by German artillery and the troops hiding behind them were slaughtered.

Oxley saw two soldiers with “tommy guns” get up and rush up the slope to attack the Germans. Both were shot and tumbled back down the hill. Medics who picked up wounded on the beach and placed them on litters were killed while carrying them to landing craft. The horror was relentless.

Oxley got tired of waiting to get killed on the beach. He saw a Landing Craft Tank (LCT) 100 yards behind him near the water’s edge. Oxley jumped out of his hole and ran towards it. That got the attention of a German machine gunner who fired bursts at him. He “ran, stumbled and crawled” until he reached the LCT. Once again, no German bullet pierced his body. However, the gunners did manage to shoot off the seat of his britches. The exhausted Oxley climbed aboard the LCT believing that it was his ticket back to England. However, a 20MM gunner on the LCT could not resist shooting at a nearby German pillbox. Unfortunately, the Germans in the pillbox returned fire and within minutes, the LCT was sinking. Once again, Oxley jumped off a sinking vessel into cold waters.

After again spending what seemed like an eternity on the beach, Oxley espied his next ride to freedom. “Coastie” LCI 93 was coming in to unload troops 150 yards from him on Easy Red sector. He ran along the beach chased by small arms fire. He boarded LCI 93, only to find out that it too was only a temporary reprieve. After landing the troops and collecting some wounded, the “93” sailed back out to the troop transport USS Samuel Chase to pick up another load of soldiers. To Oxley’s dismay, LCI 93 sailed back to the beach. On the way back to shore, Oxley told one of the crewmen on LCI 93, “I think I am a Jinx!”

As LCI 93 landed her second load of troops, sixteen crewmen fled from the nearby LCI 487, having been disabled by a mine on the beach. They ran to LCI 93 to seek refuge. That attracted the attention of German gunners who shot the “93” to pieces. With the tide going out, exposing a sandbar behind it, LCI 93 could not be retracted off the beach. She was trapped. With LCI 93 getting pounded, Gene Oxley decided to take his chances on the beach again. For the third time in a matter of hours, Oxley jumped off a sinking vessel into cold waters.

Ten miles off shore, LCI 85 pulled away from the USS Samuel Chase. The Salvage Tug (AT 89) came alongside and attempted to pump water out of the “85.” They could not pump fast enough. LCI 85 began to sink at the bow. The crew of the “85” scrambled onto the tug. LCI 85 rolled over with the bottom of her stern sticking out of the water. At 2:30PM, sailors from the tug, deployed an explosive charge on the stern. After sailing 165,000 nautical miles during her life, and earning four battle stars, LCI 85, with her “Four- Leaf Clover” sank in 14 fathoms of water. Her luck had run out.

The crew of LCI 85 huddled together on the deck of the tug. Their Skipper, Hendley sat alone, away from the crew. He broke down crying, believing that he was responsible for the deaths and wounding of the many men on the “85” that day. His guilt was unfounded but his pain was real. Those feelings of guilt would haunt him for years.

On the tug, the crew of LCI 85 was issued a Red Cross package containing a towel, sweater, pants, socks, shoes, toothbrush and razor. The clothes they were issued were intended for Merchant Mariners and were certainly not U.S. Coast Guard regulation. Fireman 1st Class S. Eugene Swiech of Chicago, Illinois was issued a yellow wool sweater and black trousers with pinstripes. His shipmate, Carmichael was similarly attired.

Back at Omaha Beach, the intrepid Oxley huddled in a foxhole, surrounded by dead soldiers for three hours. He was finally rescued by a boat sent from the destroyer USS Doyle. He spent the next day on the “Doyle” and was then transferred to another “Coastie” LCI. Oxley assisted in pumping water out of the holed LCI for the next two days until it could join a convoy back to England.

Oxley’s shipmates from LCI 85 were transported by the tug to a Landing Ship Tank (LST) in the assembly area that served as a hospital and temporary refuge for crews from vessels that were sunk. Three days later, the crew of LCI 85 was in Plymouth, England at a survivors’ camp. There, they were reunited with Gene Oxley in a raucous, joyous celebration. Oxley, whom his shipmates had given up for dead, was given the nickname the “Lucky Ox.”

Hendley wandered around Plymouth that night in search of a pub. He could not find one that was open, so he purchased a bottle of scotch from a man who peddled black market liquor. Hendley then took a train to visit his English girlfriend who lived with her mother. It was a shocking reunion for the women. They believed Hendley had been killed in action. His girlfriend, Sylvia worked at a British Navy communications center where she received a false report that all hands were lost when LCI 85 sunk. It got worse. Days later, Hendley’s father was in a movie theater in South Carolina where he saw a newsreel of the film taken by a U. S. Coast Guard photographer on the USS Samuel Chase. The film showed LCI 85 transferring wounded to the “Samuel Chase” and then listing and floundering in the water. The narrator of the newsreel announced that the crew had gone down with the ship. For a week, Hendley’s father believed that his son was dead and tried in vain to get information from the Coast Guard. Fortunately, Hendley had worked for the Washington Evening Star before the war. He sent them his eye witness account of D Day. When they received the story, Herb Corn, the managing editor, contacted Hendley’s father by phone and assured him that his son was alive and uninjured.

Back at the survivors’ camp, Carmichael grew restless. He needed a respite from the painful memories of the carnage on D-Day. He recruited a co-conspirator to leave the camp and visit a couple of fair English maidens who he knew in a nearby village. They slipped out of the survivor camp and soon they were socializing with the girls. Their fun was short lived. Few things go unnoticed in a small village, especially oddly dressed strangers. Carmichael was startled when the house was surrounded by police and armed men of the Home Guard who demanded that Carmichael and his cohort in crime exit the house. They had been reported as German saboteurs and they were being arrested. Carmichael informed the armed men that he and his companion were none other than proud members of the U.S. Coast Guard and survivors from the sunken LCI 85. He plead with his captors to return them to the survivors’ camp where his officers and shipmates would vouch for them. Reluctantly, his captors did so and Carmichael was reunited with the rest of the crew of LCI 85.

Oxley was interviewed at the survivors’ camp by a U.S. Coast Guard Combat Correspondent, Everett Garner. The interview was released for publication on June 25 and was titled “Indianapolis Coast Guardsman Has Three Ships Shot Out from Under Him In One Morning: And Loses Only Seat Of Pants.” The Coast Guard saw the public relations value of Oxley and on June 26, Oxley received orders to report to the Coast Guard Public Relations Office in London.

On June 24, Hendley submitted his after- action report for LCI 85 on D Day. He then traveled to Weymouth and located his friend Lieutenant (j.g) Henry K. “Bunny” Rigg, the Skipper of LCI 88. One of Rigg’s officers was wounded on D Day, so Hendley replaced him for several weeks. LCI 88 shuttled more troops to Omaha Beach and performed other duties. Afterwards, Hendley joined the headquarters staff of LCI Flotilla 10 at Greenway House for several months.

Farrar was shipped via hospital ship to the U.S. Navy Hospital, Portsmouth, Virginia, where he was admitted on July 29, 1944. There, he received a whole skin graft on his left gluteal region for his wound sustained on D-Day. He was granted convalescent leave and he returned to Elgin, Oklahoma. On September 9, 1944, he married Ferne Castle in nearby Lawton, Oklahoma. Farrar was awarded the Purple Heart Medal and he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for his heroism at the ramps of LCI 85 on D Day. On June 29, 1945, he was assigned to Coast Guard Operations Base, Galveston, Texas as Communications Officer and Port Security Officer. On September 1, 1945, he was transferred to Houston, Texas as the Port Security Officer. On October 3, 1945, Farrar was promoted to Lieutenant in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves.

Farrar requested to remain on active duty, but his request was denied October 24, 1945 due to a reduction of force of the military returning to peace time strength. Farrar was mustered out of active duty status in New Orleans on January 14, 1946. The following day, he began his inactive duty reserve status and returned to his job as Superintendent of Schools in Elgin, Oklahoma.

Farrar earned his Doctorate of Education from the University of Oklahoma in 1957. He retired from his position of Superintendent of Elgin Schools in 1967. He finished his career in education as the Head of the Business Department at Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma.

Farrar was an excellent athlete who was never hindered by his wound received on D Day. He and his wife Ferne raised three sons and a daughter, to whom he spoke very little about the war. Fifteen years after D Day, his fellow “Okie” shipmate from LCI 85, Carmichael, looked him up at his office at the school district. After a long conversation, they kept in touch and attended reunions for the crew of the “85.” In 1988 Farrar suffered a stroke that weakened him. He wrote his last letter October 26, 1989 and mailed it to Carmichael. He advised Carmichael that he would not attend the reunion that year but reminded Carmichael that they were to play a round of golf soon. Carmichael received the letter on October 30th. He was stunned the following day when he read in the newspaper that Farrar had died October 29. Lieutenant Arthur Farrar was buried in Old Elgin Cemetery, Elgin, Oklahoma.

Following survivors’ camp in Plymouth, England, Carmichael was shipped back to the United States where he was stationed in Port Arthur, Texas. There, he was put in charge of a 38’ picket-boat with duties to put commercial pilots aboard ships entering the inter-coastal canal at Sabine Pass. He married his sweet heart, Bette Lee Steen on March 27, 1945 and they set up house in Port Arthur. His older brother Dortis, a Navy Seabee, married Bette’s younger sister, Edna Jean.

Carmichael mustered out of the Coast Guard as a Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class September 29, 1945. He returned to Crescent, Oklahoma and found employment as a bookkeeper at the Farmers & Merchants Bank. He worked his way up the ladder to Bank President. He was employed there for 28 years. Carmichael and his wife Bette adopted their two daughters with whom he spoke little of the war.

In 1973, Carmichael took a job with the First National Bank in Okeene, Oklahoma, where he again worked his way up to the position of Bank President. He retired in 1985. He was a civic leader, serving as a board member and president of several organizations. He served on the Crescent City Council and was Mayor for four years. He also found time to be a member of the Crescent Volunteer Fire Department for 20 years and served as their Chief for 2 years.

Always the patriot, Carmichael was a lifelong member of the American Legion and always promoted the U.S. Coast Guard and LCI 85. Carmichael conducted a campaign to have Flotilla 10 honored. After years of persistence and with help from Congressman Phil Graham, Carmichael succeeded. Fifty-seven years after D Day, Flotilla 10, Group 29 was awarded the Coast Guard Unit Commendation for their gallantry on June 6, 1944. They received the award from Admiral Riker, U.S. Coast Guard at a Flotilla 10 reunion in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Carmichael was a fixture at other LCI reunions including those of the USS Landing Craft Infantry National Association. He wrote articles about LCI 85 for Oklahoma newspapers. He wrote the article: “The Life and Death of LCI (L) 85,” for the book: “USS LCI, Landing Craft Infantry, Volume I” published by the USS LCI National Association in 1993. He also submitted articles for the “Elsie Item” newsletter.

Carmichael later donated to The National D-Day Museum in New Orleans (Now, The National World War II Museum), the helmet he wore in the iconic photograph of him kneeling on the deck of LCI 85 on D Day surrounded by bodies of soldiers killed by German gunners. After the grand opening of that museum June 6, 2000, Carmichael received a letter from a man who wanted to remain anonymous. The man was a soldier who was wounded on LCI 85 on D Day. He wanted to thank Carmichael and his shipmates for saving his life.

In his later years, Carmichael suffered from esophageal cancer and weakened arteries. His condition deteriorated after his beloved wife Bette died on February 21, 2011. Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Elmer Carmichael died September 26, 2011 and was buried in Crescent, Oklahoma.

Captain Emerald Ralston of the 1st Medical Battalion, who acted heroically, saving the wounded on LCI 85, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on August 8, 1944 for his actions on D Day. On February 2, 1945, Ralston was awarded an Oak Leaf Cluster to his Silver Star Medal for gallantry in action on July 28, 1944 in Normandy, France. He survived the war and lived until age 83. He died May 22, 1989 and was buried in the National Cemetery of Arizona in Phoenix, Arizona.

Oxley became a reluctant hero and celebrity after D Day. He was promoted to Coxswain and was awarded the Silver Star Medal. While assigned to the Coast Guard Public Affairs in London, the “Lucky Ox” story was featured in newspaper articles and a live interview, short wave CBS Radio broadcast from London to New York. He was interviewed by broadcast journalist Bill Shadel. He was sent to Glasgow, Scotland for a short time before being shipped back to the United States.

The Coast Guard sent Oxley on tour throughout the Midwest at ammunition and armament factories where he told his story, raised morale and money for the war effort. He was photographed with other celebrities, Congressmen and Senators and was featured in many newspaper articles. Oxley was also featured in a chapter of the book “Sea, Surf & Hell” published in 1945. Jack Warner of Warner Brothers Studios suggested to Oxley that he write a book about himself and Warner Brothers Studios would produce a movie based on the book. The humble Oxley declined. He just wanted to return to a normal life.

Oxley mustered out of the U.S. Coast Guard as a Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class in September, 1945. At first, he worked for his brother- in- law in the landscaping business. On August 17, 1956 he married Dorothy Mae Carr in Indiana. They adopted a son and daughter. Oxley did share his wartime experiences with them. They started a new life in Milford, Ohio, near Cincinnati. There, Oxley started his own landscaping business which flourished. He purchased 99 acres of land which he used as a nursery for that business. He spent the rest of his life in Milford. He was haunted by his experience on D-Day. He became an alcoholic and later became addicted to prescription drugs. He was a chain smoker and developed emphysema. Eventually his lungs and his heart failed. The “Lucky Ox,” hero and celebrity died May 16, 1992 and was buried in Milford, Ohio.

The U.S. Coast Guard did not share Hendley’s belief that he was responsible for the deaths and wounded on LCI 85 on D Day. On the contrary, they recognized his heroics in his attempt to save LCI 85 and the personnel onboard. Hendley was awarded the Silver Star Medal and the French Croix de Guerre. Later, he was shipped back to the United States and was promoted to Lieutenant. He was assigned to Charleston, South Carolina, Baltimore, Maryland and finally, Washington, D.C. He mustered out of the Coast Guard December 14, 1945.

Hendley went back to work for the Washington Evening Star Newspaper as a reporter. He eventually lost his southern accent. He worked his way up to Assistant City Editor. While working there, he met his future wife, Barbara Louis Davidson, who was also employed at the “Star”. Hendley and Barbara married July 18, 1948 and raised two sons and two daughters. He spoke little to them about the war. In 1965, Hendley joined the Gannett Group and was the Executive Editor of the Elizabeth Daily Journal. A young copy boy at the Washington Evening Star, Carl Bernstein followed Hendley to the Elizabeth Daily Journal. Hendley mentored Bernstein and gave him his first job as a reporter. In 1966, Bernstein left the Elizabeth Daily Journal for the Washington Post as a reporter.

Hendley later became a newspaper trouble shooter, working from paper to paper. He was the Executive Editor of the Camden-Courier Post from 1968 through 1972. On October 10, 1972, Hendley’s wife Barbara died of a brain aneurysm. Carl Bernstein, then the Washington Post reporter of Watergate fame, took a break from the investigation to attend her funeral.

Later, Hendley became the Executive Editor of The Herald News-Passaic, New Jersey, from 1972 until his retirement in 1980. He came out of retirement in 1982 to help start up a new newspaper, The Washington Times as the first Managing Editor for that paper.

Hendley had contact only once with a shipmate from LCI 85 since he shipped back to the United States from England. However, in 1984, Fireman 1st Class Eugene Swiech of LCI 85, contacted Hendley after seeing him on television. He requested a reunion with Hendley on June 6, 1984. Hendley’s contact with Swiech brought back many buried memories. Before meeting Swiech on June 6, Hendley wrote an article for the Washington Times that was published on June 6. It was re-printed by the U.S. Coast Guard. It was a detailed story of his war history including the sinking of LCI 85 on D Day.

Hendley continued working at the Washington Times until his death, at which time he served as an Associate Editor. Lieutenant (j.g.) Coit Hendley Jr. died at home in Washington, D.C. on May 16, 1985 of heart failure. He was buried next to his wife Barbara in Annapolis, Maryland. Many journalists attended the funeral service. Hendley’s sons and Carl Bernstein were pallbearers.

Sadly, there are no LCI 85 crewmen alive today. May they and their “Four- Leaf Clover” find fair winds and following seas.

Research Notes & Sources

Coit Hendley Jr., Arthur Farrar, Elmer Carmichael and Gene Oxley wrote their personal wartime stories or dictated their stories to others. Of the four, Elmer Carmichael is the only one who I interviewed. This article is their story. They lived it. I merely weaved together their stories and other information obtained during my research into a chronological order of events.

Coit Hendley Jr. wrote three stories used for this article. His personal account of D Day was published in “The Coast Guard at War: Volume XI, Landings in France,” published by U.S. Coast Guard Public Information Division, 1946.

Michael Oxley, the son of Gene Oxley, sent me his father’s personal scrapbook. Inside was a copy of an undated war time document issued by a Public Relations Officer, U.S. Coast Guard, Washington, D.C. Labeled as “Immediate release/for release,” was a personal

story of D Day, written by “Coit Hendley, Lieutenant (j.g.) USCGR, formerly on the staff of the Washington Evening Star.”

The third story written by Hendley, used for this article was a story about his wartime experiences: “D Day: A Special Report” published by the Washington Times newspaper June 6, 1984. It was re-printed by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Hendley’s son, Coit Hendley III provided me with biological information and Hendley’s work history in journalism, including his mentorship of Carl Bernstein. He provided information regards to cause and date of death of Hendley’s wife Barbara.

Hendley’s son, Peter Hendley provided me with wartime photographs of his father, place of burial of Hendley and his wife Barbara, as well as specifics of Hendley’s funeral. He also provided me with a copy of his father’s orders to take command of LCI 85 in January, 1944. The source of Peter’s information was a book he was completing at the time of my research: “LCI 85: The Military Career of Lt(jg) Coit Hendley Jr. During the Invasions of North Africa, Italy and Omaha Beach on D-Day: His Papers and Photos”, published by Yewell Street Press, ISBN:978-0-9964993-6-1.

Hendley’s daughter, Dale Hendley provided me with dates when Hendley joined the Coast Guard and was released from the Coast Guard as a Lieutenant.

Arthur Farrar wrote one story used for this article. His story of his wartime experiences: “LCIs Are Veterans Now” was published December, 1944 (Vol VI, No. 9) issue of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy Alumni Association Bulletin, pp. 181-191.

Farrar’s son, Arthur R. “Ray” Farrar, provided me with wartime photos, biographical information, and military records of his father. He also provided a letter from his father to Elmer Carmichael days before he died and Carmichael’s letter to Farrar’s widow days after Farrar died.

Farrar’s son, Edwin Farrar, provided me with stories of Farrar’s marksmanship training with his .45 caliber 1911 pistol, discarding that pistol after being wounded, his German machinegun souvenirs, and the lack of any hinderance from his wound in post war life.

I found, the date of birth, date of death and date of marriage of Farrar and his wife on the web site www.findagrave.com.

Also, on that site was a photograph from a newspaper article of Farrar and notation that he was Superintendent of Elgin Schools.

I found Farrar, next of kin and war time address on the list of WWII Navy, Marine and Coast Guard casualties on the web site www.fold3.com.

Elmer Carmichael narrated one story used for this article. “The Life And Death Of LCI (L) 85” was printed in the book “USS LCI, Landing Craft Infantry”, Volume I, produced by the USS Landing Craft Infantry National Association and published through Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Kentucky, 1993.

I found Carmichael’s obituary on www.findagrave.com. Carmichael’s daughter, Deborah Rice advised me that she and her husband submitted the obituary after editing a biography her father wrote October 22, 2004. She provided me that biography as well as an article referencing Carmichael’s success in securing a Coast Guard Unit Commendation for Flotilla 10, Group 29. Deborah provided me with a photograph of her father taken at the survivors’ camp in Plymouth, England, in June 1944. She also provided me with the date of birth and death of her mother.

I interviewed Carmichael at a reunion for the USS Landing Craft Infantry National Association. He provided me with his story of his arrest after slipping away from the survivor’s camp after D Day. He described the clothing he was issued on the Tug which was different than the clothes he was photographed wearing later at the survivors’ camp.

Gene Oxley first told his D Day story at a survivor’s camp in England to Everett Garner, a Coast Guard combat correspondent. The story: “Indianapolis Coast Guardsman Has Three Ships Shot Out From Him In One Morning: And Only Loses The Seat Of His Pants,” was released June 25, 1944. I found this document in the archives of the USS LCI National Association. A research team from our Association recovered this document during one of its trips to the National Archives. I also received a wartime copy of this document in the personal scrapbook of Gene Oxley, sent to me by his son Michael Oxley. This undated document was from U.S. Coast Guard Public Relations Division, labeled for “Immediate Release.” Also, in the scrapbook were other wartime copies for immediate release by the Coast Guard Public Relations Division in Washington, D.C.: “Gene Oxley Biography,” and “Indianapolis Coast Guardsman Braves Nazi Fire: Loses Pants, Three Ships,” in which Oxley praised Hendley for his action at Sicily when he marched down a ramp so that soldiers would follow him, and Hendley not ducking behind cover while under fire on the bridge of LCI 85 on D Day.

Other copies of wartime documents in Gene Oxley’s scrapbook were: a transcript of live interview of Oxley by Willian Shandel, Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), short wave broadcast from London to the United States; the original orders dated June 26, 1944 for Oxley to report for duty in London with the U.S. Coast Guard Public Relations Office.

There were many wartime photos in Oxley’s scrapbook of him on speaking tours for the Coast Guard in the United States. There were several copies of newspaper articles in Oxley’s scrapbook reference his actions on D Day including an undated article in the “Indianapolis Star,” a St. Louis newspaper September 20, 1944; a “Daily Herald,” July 3, 1944; and an undated “Evening Standard.” There were three other unknown and undated newspapers with Oxley’s D Day experiences.

Oxley’s daughter, Vikki Lamons, provided me with information regards to Oxley’s childhood, his father’s suicide, his mother’s mental instability, the CBS live broadcast/interview, his anguish over what he experienced on D Day, his life before and after the war and his cause of death. Her brother Michael confirmed the information she provided. Vikki was able to confirm information in newspaper articles about her father, such as the story of Jack Warner offering to make a movie about Oxley, and she was able to debunk a couple of exaggerations made by others in newspaper articles to inflate her father’s pre-war accomplishments.

Andrew E. Woods, Research Historian for the Colonel Robert R. McCormick Research Center, First Division Museum at Cantigny Park, Wheaton, Illinois, contributed greatly to this article. He informed me that a soldier onboard LCI 85, Captain Emerald Ralston, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions on D Day. Andrew sent me copies of Ralston’s citations and other military records which enabled me to tell his story. Andrew sent copies of “Top Secret Neptune” landing diagrams that included a list of units and numbers of personnel carried to shore by LCI 85. One of the units listed was the 6th Naval Beach Battalion. They have an excellent web site, www.6thbeachbattalion.org. On their site I found letters dated October 21, 2002 and November 9, 2002, reference members of that unit who were killed on LCI 85 on D Day. One letter, written by Ken Davey identified those killed, including the two officers and friends of Hendley who Hendley waved to moments before they were killed.

I found a copy of Hendley’s After Action Report for LCI 85 on D Day on www.lci.org, the website for the USS LCI National Association. It is listed under archives for the “Elsie Item” newsletter, Issue # 58.

Molly Daniel

Thank you for this excellent article and details of the sources of your information. My husband is a great-nephew of Lt. (jg) Jack Hagerty, the 5th ESB beachmaster who was killed by one of the shells which hit the LCI-85 as he was preparing to go ashore. We visited Omaha Beach in 1994 and 1995 and have since learned much more about the ship, her crew, and the Army and Navy units on board. Ken Davey has been an big help to us, and my husband also attended a reunion of the 6th Beach Battalion in 2002 and spoke with survivors of the 5th ESB. Bless them all.

I appreciate very much your documenting and sharing this story.

Matt Butcher

This is amazingly well written! Difficult emotionally but should be read by everyone.

Lisa Jones

This was so interesting and informative. My dad, Charles Oktavec, was a crew member on LCI 85 during the Normandy invasion on D-Day (he was 17 years old). He never talked in much detail about that day except to say it was horrific and the boat sank. He said his job was measuring the depth of the water and calling it back to the pilot. He and Elmer Cartwright became re-acquainted later in life and came to be good friends. My dad passed away in 2012. I hope we never forget “the greatest generation”. Thank you for writing this account.

Peter Hendley

Thank you for this well-written article. My father Coit Hendley would have appreciated it. All his life he remained emotional about and barely able to discuss his experiences on D-day. It is important that they be recorded so we never forget – Pete Hendley

James P Cummings

About 1970 I worked for a CPA and attorney named Edward J. Eng in Hollywood, California. I vaguely remember him saying he was in the navy in WWII. He was Chinese American. Recently I checked online to see what had become of him. He died many years ago. I ran across a website saying he was a gunner’s mate on this ship. It also said he had been in North Africa, Salerno, and Sicily before D Day. Does anyone remember him? There was a description saying he had tattoos on both arms and his chest.

Rolf Richard Arneberg Brathen.

I wish I knew enough when I was a kid to ask my grandfather about this while he was still alive. It must of been hard to share details and so I never wanted to upset him by asking. All we had was a silent news reel clip of him being evacuated after he lost his leg. Radioman 3rd class Gordon Richard Arneberg. As an adult I now am greatful for these details. This gives us a better understanding of what he had experienced.

John France

Rolf, most of our WWII vets did not discuss the war when they returned. There were 6 million Americans in uniform during the war and most believed they were jusr one of many doing their part for the war effort. It was a different time and a different generation of people who had already endured the Great Depression before seeing the horrors of war. After the war, they just wanted to get on with their lives. It is our duty to keep their legacy alive. It is our duty to honor them. What they did for us was incalculable. God bless them all. John France

amy harbo

I was in tears reading this account of the men on LCI 85. How impressive that you gathered this information and have memorialized their valor and courage. Even those who survived gave up so much of their lives, expecting nothing in return. My dad served on LCI 39. He arrived in Europe after D Day, so missed the combat and horror. Even so, he never talked about his Navy days until he was about 80, and if anything, greatly minimized his contribution. It’s only after researching that I’ve discovered that his time in the Navy was anything but easy. Merely crossing the ocean in an LCI five times was grueling. I’m fortunate to have a lot of his letters home and a wonderful scrapbook he compiled. Thanks again for helping us remember these special men. It’s sad that Oxley had such a tough life afterwards, but how could he not after everything he experienced in that single night. God bless them and their families.