By Jeff Veesenmeyer

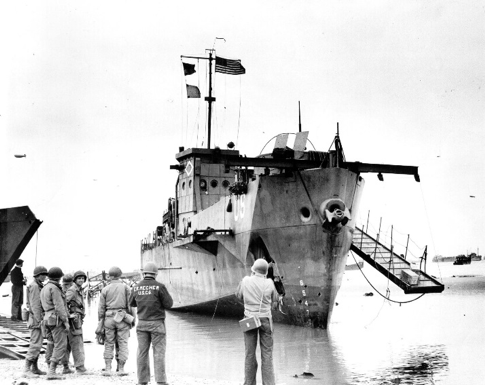

“Okay, let’s go.” Those three simple words from General Dwight D. Eisenhower set into motion the largest amphibious invasion in history. An armada of 5,300 ships would be delivering 150,000 troops, their equipment and supplies to the coast of Normandy. Among those ships were over 4,000 landing craft of all types. They included LCVPs, LSMs, LSTs, and LCIs.

Famed war correspondent, Ernie Pyle reported, “The best way I can describe this vast armada and frantic urgency of traffic, is to suggest that you visualize New York Harbor on the busiest day of the year and then enlarge that scene until it takes in all the ocean the human eye can reach, clear around the horizon. And over the horizon there are dozens of times that many.”

The memories of D-Day remain vivid for LCI sailors who hit the beaches with allied infantry troops 75 years ago. Their stories have been told through oral histories, books, magazines and our own Elsie Item. Some excerpts from those stories are reprinted here to remind us of what LCI crews experienced that morning of 6 June 1944.

Chuck Phillips – Engineering officer LCI(L) 489: Our cook, Mike Yakimo, used everything we had in the refrigerator to prepare the finest meal he could for the troops we carried. Mike was a great cook and wanted to do something special for the soldiers. I don’t recall that they were too hungry, understandably. Sometime that night, I, in my Mae West, went down to the troops with some soup Yakimo had prepared for them thinking the soup might be something their seasick stomachs could handle. These guys were seasoned soldiers, they looked at me all bundled up in my Mae West as if something might be wrong with me, but they didn’t say anything derogatory. What I remember is that they had a quiet determination. They were calm; there was no hysteria. They were stripped down lying on the bunks resting-contemplating, no Mae West’s, but holding their rifles knowing what they had to do the next morning and preparing themselves mentally to do it. As I left them, I couldn’t help thinking about the wives, children, and parents back home who might never see their husbands, fathers or sons again. I didn’t even realize the full extent of the danger they–we all–would be facing.

Gene Januzzi – LCI 530: As we waited, I sensed my smallness and loneliness among the immense forces that at last had been unleashed. I saw the glow of bombs bursting silently on the enemy shore, watched a giant outburst of anti-aircraft fire that hosed and spewed and flowered in a merry hell of light and color. I heard and saw in the light of the anti-aircraft fire the C-47s flying low-towing gliders towards the beach. They returned without gliders.

At H-hour minus two hours, the commander came up to the conn and told me to get underway slowly down the swept channel to Point Zebra, which was a ship standing just off Utah Beach. As my ship moved, the aerial bombardment and the anti-aircraft fire ended. I heard and smelled the gunfire of the Navy ships. Dawn diluted the night. As we neared Point Zebra, my eyes were on the beach. German 88s sent up geysers of water and sand at the shoreline. I stopped engines and waited for a signal from the control vessel. It was the last wait. From the vessel came a one-word semaphore message: PROCEED.

I looked at the Commander and he nodded. I got my ship underway and headed toward the beach. “All engines ahead full.” I said into the voice tube, “Steady as you go.” The wait was over.

Chuck Phillips – Engineering officer LCI(L) 489: Because of heavy cloud cover, Air Force bombers who had come in before H-hour had been unsuccessful in destroying the German defenses. Their bombs landed inland and missed the beaches. Huge concrete bunkers and smaller pillboxes held artillery. An enemy gun was strafing the beach from a bunker just above the area our troops were landing. The captain ordered the ramps back up. We began to back off. I don’t know if any of the soldiers who disembarked survived at that first attempt to land, except the ones we were able to pull from the ramps. Other LCIs around us were not as lucky. Some of them were destroyed beyond repair and never got off the beach. Seems I recall a Coast Guard LCI 91 or 92 burning on the beach all day. I still don’t know how we survived. We had experienced our first site of Bloody Omaha. Around 7:30 a.m., we were steaming as before, shaken and proceeded to AP76 to report.

James M. Loy – Admiral, U.S. Coast Guard Commandant: Throughout the invasion, four of the LCIs numbers 85, 91, 92, and 93 were lost while distinguishing themselves in the heat of battle. LCI 85 was one of the first to ram its way through sunken obstacles and successfully clear troop compartment. After unloading troops to smaller landing craft, LCI-85 struck a mine and was simultaneously struck by 25 artillery shells. Listing badly, LCI-85 returned to USS Samuel Chase and unloaded its wounded before it sank.

Edward Sciecienski – Coxswain LCI 487: As the 487 dropped her ramps I ran forward from my station on #2 gun and descended the ramp with the “Man Rope” that would assist the heavily laden soldiers going up to the beach. I was concentrating on stretching the line to the beach and falling on the small anchor to draw the line tight so that soldiers would have something to hold on to as they struggled through the surf. As I pushed through the cold waves, I discarded my Thompson .45 caliber sub machinegun that was impeding my forward motion. Amidst the thunder of artillery and mortar rounds I threw myself onto the anchor on the beach. I was not thinking that June 6 was my eighteenth birthday. My only thoughts were whether I would survive the day.

James Roland Argo – Pharmacists Mate 1/c LCI 489: To the best of my recollection, our LCI and about 5 other LCIs among LSTs, and LCMs hit Omaha Beach just at daybreak on Jun. 6, 1944. Immediately all hell broke out. The German bunkers that were supposed to have been shot out in an air raid weren’t. For two solid days our LCI was shelled. You should have seen my helmet. I wish I had saved it for my kids to see. During the invasion itself, the sick bay expanded to include the mess hall and the deck. The men on our LCI were lucky. We did not have one single casualty. The mess hall and deck were filled with men from the Big Red One and other landing craft along-side us.

Al Allen, a seaman, brought wounded men to me all day on the 6th and 7th of June. He never stopped even though he took a shot across the knee. He was a good young man. He probably saved more lives than we can count in those two days, literally hundreds and hundreds. I don’t know how he maintained the stamina to keep bringing the injured from the beach onto the LCI. I patched these men up the best I could and got the really injured ones transferred to hospital ships. When Allen couldn’t get the injured to me, I went to them on the beach. When I would jump into the water with all my gear and medical kit, I would nearly go under. The waves with the weight of my gear were not a good combination for jumping into the ocean. It was so loud for two days with shelling and bombing. I’d say, “Watch out behind you Allen” and he would duck, or he’d say, “Hit the deck Doc” and I would hit the deck. We watched out for each other. It seems a miracle now that we did not lose one man on our LCI on D-day. Sometimes the air was so full of fire that it seems impossible that any of us survived.

There were 4,414 confirmed allied troops killed in action on D-Day. Many of those are buried in the American Normandy Cemetery. Sixteen LCIs were destroyed.

John Cahill

My dad took a picture of “US 91” more than a year after d-day. It was still in the same spot in the water near omaha beach. He was in US 91 with the 147th combat engineers. He lived an honest, hardworking life along with my beloved mom. I miss them countless times a day.

Joe Ajdinovich

John,

I periodically google LCI 91, as my Father was on the LCI as well. My Father was on the port ramp when the LCI was struck by the “88”. Company B, 147th Engineers. I attended the last 147th Reunion with my parents in about 2008 in Charleston, S.C. I’m glad that our Father’s survived the ordeal and the war.

Best Regards,

Joe

Bill Ward

Joe,

I am doing research on one of our County’s D-Day casualties. Robert Pitts of Kennard, Indiana was on LCI91 when it was hit and never found. It is believed that his body was one of the chared 25 bodies that was never identified. A few months ago I saw where one of them was identified via DNA giving us hope that Robert may be ID,d soon.

Joe Ajdinovich

Bill,

Service Member

Pfc. ROBERT PITTS

Return to Service

Member Profiles

Conflict

Service

Status

WORLD WAR II

UNITED STATES ARMY

Unaccounted For

On June 6, 1944, U.S. Coast Guard personnel manned the infantry landing craft USS LCI(L)-92 which carried approximately 25 crew members and 200 soldiers for the D-Day landings at Normandy, France. While off the coast of Omaha Beach, the landing craft was hit by enemy shells and mortar fire before it struck a mine that ignited fuel in its forward troop compartment. The men positioned inside the compartment were killed instantly as intense fire spread throughout the vessel, which was ultimately burned out and abandoned on the beach. The intensity of the flames prevented the recovery of the remains of twenty-four men from the troop compartment.

Private First Class Robert Pitts Jr., who entered the U.S. Army from Indiana, served with the 60th Medical Battalion, 500th Medical Collecting Company, 60th Medical Battalion. He was aboard LCI(L)-92 when it burned on June 6, 1944. He was killed during the incident but his remains were not recovered. He is still unaccounted-for. Today, Private First Class Pitts is memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

Based on all information available, DPAA assessed the individual’s case to be in the analytical category of Active Pursuit.

If you are a family member of this serviceman, you may contact your casualty office representative to learn more about your service member.

Pfc. ROBERT PITTS

Unit

LCI-92; 60 MEDICAL BATTALION

Historical Country of Loss

France

Body of Water

ENGLISH CHANNEL

Current Country of Loss

FRANCE

Home of Record* IN

*Home of record is the city and/or state where the service member joined the service. This may not be the same location as where the service member was from.